To understand SkyWater’s origins, one must first rewind to the convergence of national security and semiconductor manufacturing. For decades, the U.S. military and intelligence agencies relied on advanced microelectronics built on American soil. Semiconductors powered guidance systems, radars and signal processors from the Cold War era onward.

At the same time, a structural shift in the industry was underway. While many U.S. integrated device manufacturers (IDMs) used to design and manufacture their own chips, manufacturing gradually shifted overseas — first for assembly and test, later for memory and logic production — as leading-edge fabs became more expensive to build and maintain.

This migration raised a concern: when critical manufacturing moves offshore, the risk of supply-chain interference, IP theft, counterfeit devices and tampering increases. The U.S. government responded by instituting programs like the Trusted Foundry Program to ensure secure, accredited domestic chip production.

Meanwhile, the relentless rise in fabrication cost (“Rock’s Law”) strained smaller fabs and IDMs. Some players chose to spin off or divest their manufacturing operations rather than chase sub-10 nm nodes with enormous capital outlays.

![]()

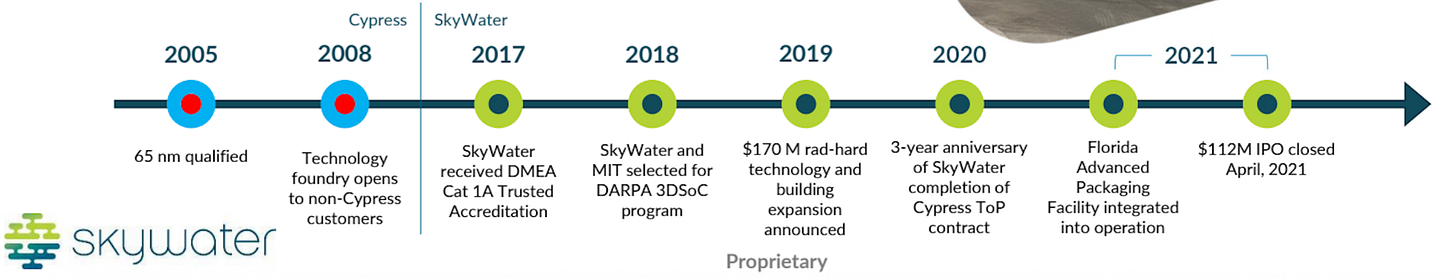

In March 2017, SkyWater Technology was formed by acquiring the wafer-fab facility in Bloomington, Minnesota from Cypress Semiconductor. Cypress sold the subsidiary owning this fab for roughly $30 million.

The facility itself had a long history: it originated as a 1991 spinoff from Control Data Corporation and later became part of Cypress as “Cypress Minnesota Inc.”

The logic behind the deal was straightforward. Cypress, as an IDM, wanted to scale back its manufacturing footprint and focus on higher-margin operations. By selling the fab to SkyWater — backed by the private-equity firm Oxbow Industries — and then contracting SkyWater to produce wafers, Cypress lowered its fixed manufacturing burden.

For SkyWater, Cypress became the anchor customer while the company sought to attract additional commercial and government customers.

Just 19 days after the acquisition announcement, SkyWater achieved Category 1A Trusted Foundry accreditation from the U.S. Department of Defense.

This positioned SkyWater as one of the few fully U.S.-owned foundries capable of manufacturing secure microelectronics — a key differentiator in a market where most pure-play foundries are foreign-owned.

From the beginning, SkyWater did not attempt to compete with leading-edge Asian foundries operating sub-10 nm nodes on 300 mm wafers. Instead, its strategy centered on a 200 mm fab focused on custom, specialty, mixed-signal, rad-hard, MEMS and advanced packaging technologies. This specialization created a clear niche: high-value, lower-volume, high-reliability applications.

One of SkyWater’s most distinctive ideas is its “Technology as a Service” (TaaS) model. The company recognized that a traditional high-volume foundry approach was unrealistic for a smaller domestic fab, so it blended process development, prototyping and volume manufacturing into a unified service.

Practically, customers could begin with early-stage device concepts, co-develop custom processes with SkyWater engineers, qualify those processes and then manufacture the resulting devices in the same facility.

This gave SkyWater two advantages:

The model built upon the specialty-foundry work established when the fab was under Cypress and expanded it to newer domains such as photonics, quantum devices, rad-hard technologies and heterogeneous integration.

By 2021, SkyWater’s strategy began to show clear results. Revenue concentration from Cypress had dropped from near-100 percent at founding to under one-third by early 2021. The company had successfully diversified, winning new customers across government, aerospace, industrial and commercial markets.

In April 2021, SkyWater went public under the ticker SKYT to raise capital for expansion. At the time, the company also outlined plans to expand its presence in advanced packaging and heterogeneous integration — areas expected to capture increasing value as Moore’s Law slows.

A major milestone came in June 2025 when SkyWater acquired Infineon’s 200 mm “Fab 25” in Austin, Texas. This facility added roughly 400,000 wafer starts per year, significantly expanding SkyWater’s U.S. manufacturing footprint. With Austin, the company gained additional capacity for embedded processing, RF, power, memory, mixed-signal and automotive applications.

SkyWater occupies a unique position within the U.S. semiconductor ecosystem. It operates at the intersection of domestic manufacturing, foundational-node processes, specialty technologies and national-security requirements.

While leading-edge fabs dominate news cycles, many mission-critical applications — from aerospace systems to industrial sensors — rely on mature, reliable technologies. SkyWater’s focus on these foundational nodes gives it an increasingly important role as supply-chain resilience and geopolitical competition intensify.

Furthermore, its trusted-foundry accreditation provides assurance to government and defense clients needing secure, U.S.-based production for sensitive electronics. Instead of competing directly with global giants, SkyWater has positioned itself as the go-to foundry for secure, high-reliability, often low-to-medium-volume manufacturing.

Despite its strong positioning, SkyWater faces several structural challenges. Foundry operations remain extremely capital-intensive, and maintaining competitiveness in specialty technologies still requires steady investment. While avoiding the bleeding-edge race helps, the company competes with overseas foundries offering lower costs on similar mature nodes.

Diversifying the customer base is another ongoing objective. A trusted-foundry designation brings advantages, but the company still operates in commercial markets where pricing pressure is real. Balancing government demand, R&D activities and commercial production will remain a complex task.

Scaling the workforce, ensuring process stability across expanded capacity and integrating newly acquired fabs (such as the Austin facility) also add operational complexity.